India, with its fascinating history and immense climatic diversity, is a true Aladdin’s cave for anyone interested in nature and, particularly, in medicinal and aromatherapeutic plants. It is the seventh largest country of the world, criss crossed by historic trade routes and home to the ancient Indus Valley Civilization, where – as archaeological discoveries prove – first known distillations were taking place already over 4500 years ago.

The diversity of Indian culture, a blend of still surviving ancient and varied local customs and the coexistence of the world’s major religions, not only shaped the region’s history but also helped develop and preserve some of the most complex medicinal systems (Ayurveda and Unani medicine) and traditions (e.g. production and use of attars).

45,000 species of wild plants are found in India out of which over 33% are endemic and several species are not found anywhere else. 7,500 species are in medicinal use for indigenous health practices and almost 300 are used for production of essential oils.

India is also a home to 195 Red Listed Medicinal Plants species and this list includes the famous Mysore sandalwood (Santalum album L.) Also known by its Sanskrit name of ‘Chandana’ (or ‘Chandan’ in Hindi) it is currently listed as ‘vulnerable’ – only one step away from becoming an endangered species. Sandalwood is mentioned in Vedas and records show that in Early Vedic period (4000 years ago) sandalwood was exported to Western Asia and Egypt. It is also one of the most sacred herbs of Ayurveda. The species is threatened by over-exploitation and changes to habitat, mainly through agriculture, land-clearing and fires. Indian legislation protects the species, and cultivation is researched and developed. Neither is a simple or straight forward task…

My journey

My first encounter with the sandalwood tree happened right at the front of the breath taking Taj Mahal, where few chandans grow in the charbagh – the traditional Mughal paradise garden – laid out between the Great Gate (Darwaza-i rauza) and the front of the mausoleum. The place had such an impact on me that, despite the years gone by, I can still remember the exact location of these trees!

The often heart stopping beauty of India has cast a spell on me long time ago and while gathering ideas for a trip to yet another corner of this vast country I came across some intriguing snippets of information and the idea was suddenly born – I shall go in search of the few surviving sandalwood forests.

Sandalwood is mainly found throughout the central part of Indian subcontinent – the Deccan Plateau. The total extent of its distribution is approximately 9000 square km of which 8200 square km are located in the states of Karnataka (Bandipur Wildlife Sanctuary – ex-maharaja’s shooting grounds – in Mysore area) and Tamil Nadu (Mudamalai Wildlife Sanctuary area). Chandan forests can also be found in Andhra Pradesh and in Marayoor and Kadamanpara/Punalur areas in Kerala.

Sandalwood is mainly found throughout the central part of Indian subcontinent – the Deccan Plateau. The total extent of its distribution is approximately 9000 square km of which 8200 square km are located in the states of Karnataka (Bandipur Wildlife Sanctuary – ex-maharaja’s shooting grounds – in Mysore area) and Tamil Nadu (Mudamalai Wildlife Sanctuary area). Chandan forests can also be found in Andhra Pradesh and in Marayoor and Kadamanpara/Punalur areas in Kerala.

I decided to head south, to the Western Ghats. The trip started in Mumbai and a short flight later we were surrounded by the lush beauty of the ‘God’s own country’ – the southern state of Kerala. The journey led us from the spice godowns of old Ford Kochi, through lush spice plantations and puzzle-like tea gardens of Munnar, to the Elephant Mountains (in Western Ghats) and their treasure – sandalwood forest. But I was not sure of its exact location and enquiries made on the way were not very encouraging. In fact not many were willing to talk about sandalwood, some even pretended not to know about such thing! As we made our way through miles and miles of winding Keralite roads my heart was filling up with dread… Will I find it at all…?

When I did finally find it, the forest was surrounded by fences, myths and a fair bit of red tape.

When I did finally find it, the forest was surrounded by fences, myths and a fair bit of red tape.

I stood by the road looking through the fence at those rather small and insignificant trees – with grey bark and small leaves – wondering why this tree has been evoking such reverence, such strong emotions and passion, why would it lead people to become thieves and smugglers. I sniffed the air – the forest did not even smell of sandalwood at all! It was only when I finally got permission of the Warden of the local Forest Department, when the guarded gate opened and I gained access to the Government’s Sandalwood Depot in Marayoor, that everything became clear…

The law

The Kerala Forest Act, 1961 (4 of 1962) has no special provision for the protection of sandalwood. However, the rapid depletion of the forests prompted introduction of changes and sandalwood trees are now government controlled and protected by law. Export of sandalwood is now banned. Only few companies, like for example incense making Japanese ‘Baieido’, who have been trading with India for over 300 years, can obtain it. All sandalwood trees belong to the government!

The Kerala Forest Bill of 2008, states: ‘no owner of any land, including a plantation […] shall, without previous permission in writing of the authorised officer [Principal Chief Conservator of Forests], cut, uproot, remove or sell any sandal tree in the land in his possession or ownership’. It also clarifies that: ‘ “sandalwood” means any portion of sandal (Santalum album) tree and includes bark, leaves and roots thereof, whether containing heartwood or not and whether in the form of roots, billets, pieces (sawn or otherwise) chips, (whether coloured or not and whether mixed with other ingredients or not) sawdust, spent wood, flakes or pulp’. In practice it also means that even a dead tree – wind fallen or dangerous to life or property – cannot be removed without written permission.

The law prohibits – unless licensed – possession and transport of sandalwood as such and sandalwood essential oil in quantities in excess of one kilogram for the wood and 100g for the oil.

The Bill also defines the penalty ‘in any case of forest offence having reference to the cutting, uprooting or removal of a sandal tree or any part of sandal tree, the offender on conviction, shall be punishable with imprisonment for a term which shall not be less than three years but may extend to seven years and with fine which shall not be less than ten thousand rupees but may extend to twenty five thousand rupees’. Second or subsequent offences will be punishable with longer prison sentences and higher fines. Despite this theft of sandalwood tress is a rather common occurrence!

The Bill also defines the penalty ‘in any case of forest offence having reference to the cutting, uprooting or removal of a sandal tree or any part of sandal tree, the offender on conviction, shall be punishable with imprisonment for a term which shall not be less than three years but may extend to seven years and with fine which shall not be less than ten thousand rupees but may extend to twenty five thousand rupees’. Second or subsequent offences will be punishable with longer prison sentences and higher fines. Despite this theft of sandalwood tress is a rather common occurrence!

All tees are marked and recorded by the government and if you have a sandalwood tree on your land you are responsible for it! Some people employ guards to ensure the safety of the trees…

The work of the Forest Officers in Marayoor

The officers of the local Forest Department have their work cut out. It involves:

- Protection of sandalwood trees and round-the-clock vigil

- Regeneration and growing trials

- Collection and storage of dead and wind- or animal- (elephant) fallen sandalwood trees

- Seizure and storage of stolen sandalwood

Neither of which is simple or straight forward.

The terrain itself is a major problem. The large, rugged and mountainous area, which is also home to free roaming elephants, makes surveillance dangerous and difficult. The forests are spread over 63 square kilometres and cut through by villages, agricultural land and pastures. Only 15 sq. km. are categorised as a sandalwood reserve. In the once lush sandalwood forests of the area, only 60.000 trees with trunk diameter over 30 cm survive. During 2001-2004 the smuggling of sandalwood in Kerala increased and threatened the very existence of the species. In 2004, nearly 2,600 sandal trees were stolen from Marayoor forests!

In 2007 the Marayoor Forest Department fenced off four sandalwood reserves spreading across 500 acres to protect the trees from cattle grazing and elephants (and thieves, of course).

In 2007 the Marayoor Forest Department fenced off four sandalwood reserves spreading across 500 acres to protect the trees from cattle grazing and elephants (and thieves, of course).

On the way to the depot we also saw ‘Sandal regeneration experimental plot’. This is a vital part of the regeneration programme where nearly 200.000 sandalwood saplings are being reared to replenish Marayoor forests.

Why is it so difficult to grow sandalwood trees?

One could ask why cannot young trees be grown from seeds and simply planted out to form new, young forests.

One could ask why cannot young trees be grown from seeds and simply planted out to form new, young forests.

It is true that sandalwood has a certain, although not very strict, climatic requirements. However, the germination from seed is difficult and unreliable. The studies show that only seeds that passed through the digestive system of birds would produce strong seedlings!

To make matters more complicated Santalum trees are hemi–parasitic. For the first 7 years of its life chandan tree will draw nutrients by ‘tapping’ into the roots of other tree species (with an adaptation of its own roots – haustorium), but without major harm to its hosts. An individual sapling forms a non-obligate relationship with a number of plants and this is why each one is usually grown next to four to five host trees. In practice this means that extra space and management of host trees in needed too. Within the ‘sandal regeneration plot’ each sapling is allocated a space of 9 square meters!

Sandalwood

Synonyms: Chandan, East Indian sandalwood, white sandalwood

Also called the Great Receiver due to the oil’s ability to absorb the aromatic molecules of other oils (hence its use in true traditional Indian “Attars”).

The trees naturally produce suckers and, providing that they are well rooted, they seem to be the best way of propagation. Special cages are placed around them for protection from grazing cattle.

The growth is very slow. Commercially valuable sandalwood is at least 40 years old!

Sandalwood trees seem to be doing very well on their own, and often appear in places they were never seen before, but so far all human attempts of proliferation of Santalum species, by means of artificial propagation, yielded very little success. It is not yet fully understood what exact conditions are needed to help the tree to thrive. Despite the efforts, studies and trials, we have still not been able to unravel this nature’s mystery.

In India sandalwood trees are considered to be ‘sacred’ or ‘divine’ and as some say, ‘divine cannot be manipulated’!

Inside the Sandalwood Depot

It took me a while to convince the officers at the Forest Station to even let me speak to ‘The Warden’ (Forest Range Officer). ‘The Depot is not a tourist attraction’, ‘This is a government property – cannot allow access!’ they said. And of course, they were right but I could not just leave without finding out more! In the end, after comparing the name on my business card to the name under another article in an older copy of the Aromatherapy Times, they relented and led me to the Warden’s compound where I was to present my ‘case’! The Warden came out to see me on the veranda, listened patiently to my explanations and just when I was running out of things to say he granted his permission. I was in! As we walked deeper into the compound I could suddenly smell it – the cool, creamy, delicious and absolutely exquisite aroma of the sandal heartwood! I have never smelled anything like this before… I was overwhelmed!

As we wandered around the open air buildings filled with tones of neatly stuck sandalwood roots, trunks, branches and sacks of chips, the Forest Officer – Mr Abdul Khareem – explained to me some of the aspects of their work.

As we wandered around the open air buildings filled with tones of neatly stuck sandalwood roots, trunks, branches and sacks of chips, the Forest Officer – Mr Abdul Khareem – explained to me some of the aspects of their work.

Healthy sandalwood tree, growing in favourable conditions, will start forming the scented heartwood in its 10th year. It will only be 3m high and the trunk will have no more than 10 cm across. It will take another 10 years before the hardwood will start to form more rapidly. Sandalwood tree is considered to be ‘mature’ at the age of 30 but the ‘best’ are 20m high and 50-60 years old specimens.

No trees are being cut down in the forests of Marayoor. Only wind- or elephant-fallen trees are collected and brought to the depot. When affected by sandalwood spike disease the trees die (within 1–2 years after the appearance of visible symptoms) but they retain the oil for many years. Such trees are also collected.

If a dead or damaged tree needs to be removed it is carefully uprooted (roots are highest in oil content). The usual time for this is just after monsoon, when the ground is moist and the process is not so labour intensive. The branches not containing any heartwood will be cut off first while those containing some are sawn off as close to the trunk as possible. The trunk is then carefully cut into the ‘billets’ (3’6’’) and each piece is immediately marked and logged in. Even the saw dust is preserved!

To prevent the loss of wood sometimes the tree is ‘reassembled’ on the ground to make sure that all parts are there. The roots, branches, billets and the saw dust are weighed before being transported to the depot.

Once in the depot, bark and most of the sapwood are stripped and disposed of as they do not yield any essential oil. The layer of sapwood closest to the heartwood might contain a tiny amount of fragrance and it will be preserved as it can be used for incense making. The roots, trunks and branches are then sorted out and graded.

Once in the depot, bark and most of the sapwood are stripped and disposed of as they do not yield any essential oil. The layer of sapwood closest to the heartwood might contain a tiny amount of fragrance and it will be preserved as it can be used for incense making. The roots, trunks and branches are then sorted out and graded.

There are 13 grades of wood:

- Grades 1-5: larger pieces without any cracks, 10kg or more and at least 1m long, will be used for sculptures and carvings (temples)

- Grades 6-8: smaller pieces, with cracks, will be reserved for medicinal use (ayurvedic ‘kashaya’) and cosmetic industry (inc. soap making)

- Chips : will be used for essential oil distillation

Even the smallest and roughest chips of wood are carefully collected and bagged. In fact, the whole depot was so well organised and neat that one could not even dream about picking up a chip from the ground as a souvenir!

The value of sandalwood

Marayoor’s sandalwood is the best in the world. It is particularly valued because of its high oil content, around 6%! The market price is approximately £48 per kg of wood. The Government estimates that the black market price reaches £27 per kg of wood. The oil costs over £1350 a kilogram! That is almost as high as gold!

The thieves

The thieves

The forest officers are also involved in the often dangerous work of tracing and seizing the stolen wood. Seized sandalwood is brought to the depot to be stored – each piece marked and logged in. It will be stored in locked ‘cages’ until the court proceeding are finished. Make no mistake – seizure of stolen wood is not a rare occurrence!

Just in March 2011 not only a vehicle carrying 100 kg of sandalwood was intercepted at Marayoor but over 600kg of sandalwood was found and seized in the neighbouring state of Tamil Nadu. In the same month yet another forest officer was beaten to death by sandalwood smugglers in the forests in Adilabad in Andhra Pradesh.

Perhaps some of the thieves are craving the ‘fame’ of the legendary forest bandit Veerappan (1952 – 2004). Regarded by some as an Indian Robin Hood, Veerappan was guilty of killing over 180 people (including senior police and forest officials), kidnapping, poaching ivory (200 elephants) and felling and smuggling of about 10,000 tonnes of sandalwood worth over 13 million pounds from within a 6,000 km² area in the states of Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu. He had a price of 50 million rupees (£ 675k) on his head, but evaded arrest for 20 years until he was killed by police in 2004.

Distillation of Sandalwood Essential Oil

The outbreak of the First World War cut off the traditional export markets for sandalwood – out of the 1313 tonnes of sandalwood offered for sale in 1914-15, only 70 tonnes could be sold. The Government decided to open their own factory for distillation of the wood in the state of Karnataka. A factory in Bangalore and later, a bigger unit in Mysore were set up.

Did you know…

Sandalwood has many spiritual significations. Sandalwood paste is used in Hindu religious rituals and ceremonies to purify the space. The paste is also applied to the forehead to bring the devotee closer to the divine. Sandalwood logs are traditionally used to build funeral pyres of the important and wealthy Hindu. At the time of Mahatma Ghandi’s death in 1948, there was not enough sandalwood in India for his funeral pyre, so logs were imported from Australia for the state funeral ceremony. 600kg of sandalwood were used.

At the moment there is only one legal (government owned) sandalwood distillery in Kerala (24 units have been caught distilling without license and closed down). In July 2010 Chief Minister V.S. Achuthanandan laid the foundation stone for a government sandalwood oil factory at Marayoor where the oil from the fallen and seized trees is now distilled (since 2011).

In the past, yearly auctions were set up to sell the wood collected at the depot, but it is now used by the oil factory. It was predicted to produce 400 kg of oil in the first year, 480 kg in the second year, 500 kg in the third year and to reach its full capacity of 640 kg in the fourth year (2015).

On reaching full capacity, the factory will require 20 tonnes of sandalwood every year. Initially, sandalwood seized by the Forest and Police Departments and dead and wind-fallen trees in forest areas will be used. The government has enough stock of sandalwood to meet the factory’s requirements for a good number of years.

There are no plans to open this factory to the tourists.

Sandalwood factory in Mysore is open to tourists. Visit it to buy authentic incense sticks and pure sandalwood oil (£8.85 for 5ml). The factory is located about 2km south-east of the Maharaja’s Palace, off Mananthody Rd. Guided tours are also available to show you around the factory, and explain how the products are made. Open: Mon.-Sat. 9.30am-11pm & 2-4pm.

Don’t forget to get some Mysore Sandalwood Soap – it has natural antimicrobial and hydrating properties, making it an ideal cleanser for gentle, sensitive, and ageing skin. (The soap is often available from good Indian supermarkets in the UK.)

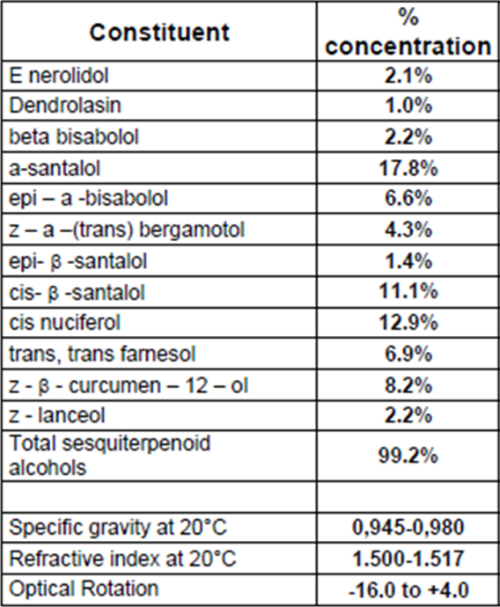

Chemical constituents of sandalwood oil

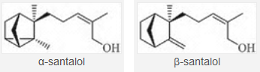

The main constituent of sandalwood oil is santalol. This primary sesquiterpene alcohol forms more than 90 % of the oil and is present as a mixture of two isomers, α -santalol and ß-santalol, the former predominating. The characteristic odour and therapeutic properties of sandalwood oil are mainly due to the santalols (beta-santalol being the most important aroma character impact compound).

α-santalol – has a relatively weak, slightly woody odour reminiscent of α-cedrene

β-santalol – has a typical sandalwood odour, with powerful woody, milky and urinous tonalities

The other constituents reported in sandalwood oil include:

- hydrocarbons: santene, nor-tricycloekasantalene and α- and ß-santalenes;

- alcohols: santenol and teresantalol;

- aldehydes: nor-tricycloekasantalal, and isovaleraldehyde;

- ketones: l-santenone and santalone;

- acids: teresantalic acid occurring partly free and partly in esterfied form, and α-and ß-santalic acids

A search of the research database Pub Med for Sandalwood Oil yields very interesting results.

- Several papers have been published demonstrating sandalwood’s (α-santalol) ability to prevent skin cancers caused by both UV radiation and toxic chemical exposure.

- Sandalwood has also been shown to improve sleep — in a Japanese study, topically applied sandalwood oil significantly reduced the total waking time when sleep/wake cycles were investigated.

Some of the recent cancer research involving sandalwood oil includes the following:

- Sandalwood oil increased antioxidant capability of liver cells in vivo (Banerjee et al, 1993).

- Santalol from sandalwood oil prevented skin papilloma development by inhibiting DNA synthesis in cancer cells (Dwivedi et al, 2003).

- Santalol from sandalwood oil was shown to be effective in decreasing ultraviolet B-induced tumour initiation, promotion, and carcinogenesis (Dwivedi et al, 2006).

- Santalol from sandalwood oil induced apoptosis in human skin carcinoma (Kaur et al, 2005).

Ayurvedic applications of sandalwood:

- Sandalwood powder is mixed with water into paste, and applied medicinally to relieve Pitta heat conditions: sunburn, acne, rashes, fevers, herpes, and even infectious sores and ulcers.

- Sandalwood is a wonderful meditation tool. Its sedative property dispels stress and calms the nervous system. Burning incense and using a sandalwood mala (Prayer beads) for japa (puja, prayers, meditation) is believed to help to quiet the mind.

- Essential oil ‘applied on the third eye awakens intelligence and lifts depression’.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank again The Warden of the Marayoor Forest Division for granting his permission and allowing me to get a behind the scenes view and better understanding of the work involved in preservation of Indian sandalwood. Thank you to Mr Abdul Khareem of the Forest Department for the valuable information, his patience and his interest in the work of the IFA. ‘Thank you’ to our friend and fantastic driver Jomon Mathew for taking such a great care of us and all the help throughout the trip. And to my Husband, of course, who keeps taking photos when I get too excited to even think about it

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

SANDALWOOD ESSENTIAL OILS

Many species of plants are traded as “sandalwood”.

Within the genus Santalum alone, there are more than nineteen species.

The most important species for aromatherapy use are:

Santalum album

- Indian or East Indian or Mysore sandalwood

- Sanskrit: chandan

- at least 4000 years of use – one of the oldest known aromatic materials

- steam distilled or CO2 extracted

- ecological status: vulnerable

- every sandalwood tree in India belongs to the government

Santalum spicatum

- Australian sandalwood

- native to semiarid areas at the edge of Southwest Australia

- harvesting controversy -Some maintain that the government regulated sandalwood tree plantations are not sustainable as the trees are not doing well. There have been reports that some producers use a combination of solvent extraction and subsequent steam or vacuum distillation to produce the essential oil

Santalum austrocaledonicum

- New Caldedonian sandalwood or Pacific sandalwood

- New Caledonia and Vanuatu

- very little remains of it in its natural habitat, due to logging

- the government imposed restrictions on the amount of wood that could be logged – the harvesting of the trees is closely monitored by government and for every tree felled, three are planted in its place

Please note:

- West Indian Sandalwood – Amyris balsamifera – is an unrelated species belonging to the botanical family Rutaceae

- Bastard sandalwood – Myoporum sandwicense – is also unrelated and belongs to the botanical family Myoporaceae

- African sandalwood, also known as Muhuhu – Brachylaena hutchinsii – another totally unrelated species from the botanical family of Asteracea

Isobornyl cyclohexanol is a synthetic fragrance chemical produced as an alternative to the natural sandalwood oil.

As the struggle to save Mysore sandalwood from extinction continues the ethically conscious aromatherapy practitioners have been looking for a suitable replacement… Few obvious alternatives have been investigated – the Australian sandalwood and Pacific (also known as New Caledonian) sandalwood.

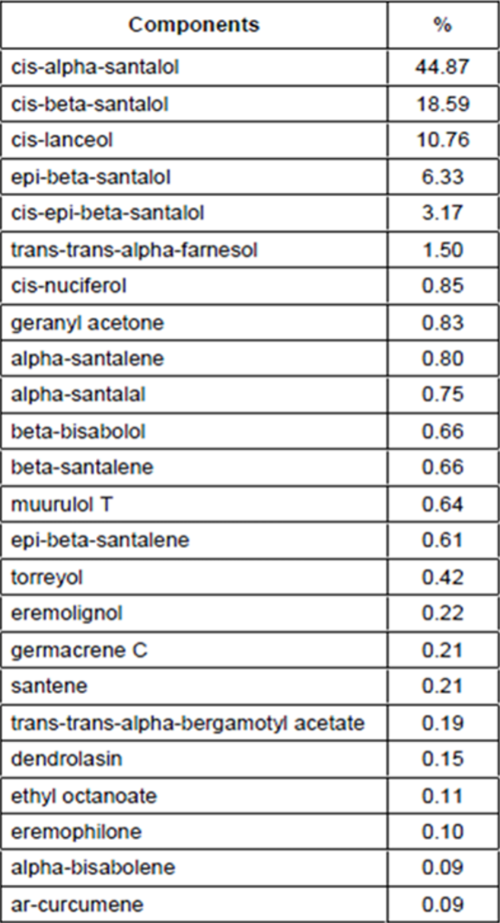

The content of the santalols as well as the aroma characteristics are being taken into account. I have included the chemical composition of the sandalwood oils below.

Mysore/Indian Sandalwood

Santalum album

Chemical make-up;

- up to 90% santalols, which are ‘responsible’ for the oils properties;

- santyl acetate and santalene, and other minor constituents

Australian

Sandalwood

Santalum spicatum

Chemical make-up:

- santalols: 5%

- Aroma: distinctively different

Pacific/New Caledonian sandalwood

S. austrocaledonicum

Chemical make-up:

- santalols: 72.96%

- Aroma: very much like Mysore sandalwood!

It is obvious that Pacific sandalwood oil is a ‘closer match’ but as the ecological status of its source is now listed as a globally endangered species, ethically conscious aromatherapy practitioners should consider using the Australian Sandalwood oil (Santalum spicatum) or Autralian-grown Santalum album.