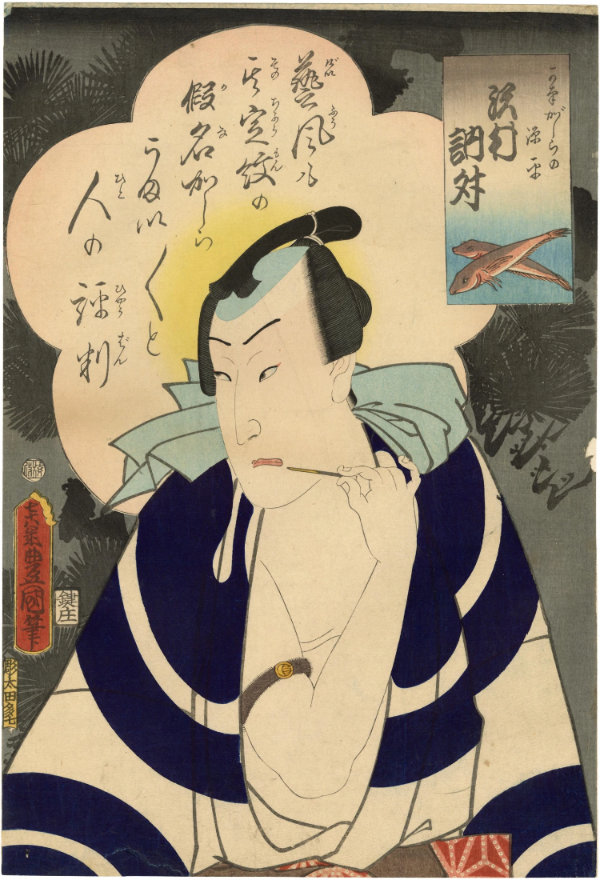

Kuromoji is strongly rooted in Japanese history, traditions and arts. It even appeared on some well-known woodblock prints! Folklore studies note that in Niigata prefecture ‘it is said that Kuromoji is the tree of a mountain-god and it is, therefore, treated respectfully.’ The essential oil of Kuromoji has been used to scent cosmetics and exported as a fragrance. In recent years it has been growing in popularity and many aromatherapists felt it may be possible to use it in place of the essential oil of rosewood (Aniba rosaeodora).

The Kuromoji Tree was first described in 1712 by a German traveller, naturalist and physician, Engelbert Kämpfer, whose writings are a valuable source of information on 17th-century Japan. It has been named and classified as Lindera umbellata in honour of Swedish botanist and physician Johann Linder (1676-1723) by botanist Carl Peter Thunberg, who in 1783 dedicated to Linder a taxonomic genius within family Lauraceae – the linderas.

‘Umbellata’- Latin for ‘in umbels’ – in this case relates to the shape of the flower clusters.

Apparently, an illustration of the kuromoji branch was included in one of the editions of the ‘Chemist and Druggist’ in 1895′ (47, 1895, 502)

Common names: In England and other English speaking countries Kuromoji is known as a ‘spicebush’ due to a scent of the twigs when they are broken off. It is sometimes called a ‘black willow’ or simply ‘Lindera’.

Japanese name’ Kuromoji’ literally means “black words” – ‘kuro’ = ‘black’, ‘moji’ stands for ‘words/kanji (japanese ‘letters’)’. The etymology of the name is not quite clear. In some regions of Japan it is also known as ‘kuro-momiji’ (black maple)

Taxonomy:

Kingdom: Plantae (Plants)

Phyla: Magnoliophyta (Flowering plants)

Class: Magnoliopsida (Magnoliids)

Order: Laurales (Laurales)

Family: Lauraceae (Laurel family) Juss.

Genius: Linders (Spice bush) Thunb.

Species: umbellata (Kuromoji) Thunb.

This specie may be further divided into 7 varieties, including:

Lindera umbellata var. umbellata Thunb called Kuromoji

Lindera umbellate var. Momiyama also called hime-kuro-moji

Lindera umbellate var. Makino known as oba-kuro-moji

Lindera umbellata, is a deciduous shrubby tree native to the cool or warm temperate zones of Japan. It is commonly found in the mountainous region of Shima Watari Hokkaido, Honshu, Shikoku, Kyushu and in China. Kuromoji trees grow wild on the edges of deciduous forests.

Sprouts and young leaves of Lindera umbellata

A small sized tree (less than 3 meters) with rounded habit and elliptical, thin, textured leaves produces dense umbels of fragrant star-shaped greenish yellow flowers before the new foliage emerges in spring. In autumn nearly black pea-sized berries clearly visible against brilliant yellow leaves follow the flowers.

Attractive from spring to autumn Kuromoji found its way into the garden design and is often planted in the Tokyo region. In Osaka summers are too hot for it but it can be seen on the hills in the countryside beyond the city.

Pretty flowers and fruit-bearing branches are used in ikebana (traditional flower arrangements). The tree is also used in ‘bonsai’, Japanese art of miniaturization of trees.

Kuromoji is greatly admired for its aromatic foliage and bark. Creamy–white and fine-grained wood is covered by spotted, grayish brown bark ageing to black. The wood is flexible and hard to break, making it an ideal material for… toothpicks. In fact this is how Kuromoji’s ‘career’ has started!

The Toothpick Tree:

The idea of cleaning one’s teeth with a twig or a ‘yoji’ (toothpick) was born in India from which, together with Buddhism, it was brought to China, Korea and Japan in 538 AD. The popularity of toothpicks passed through from Buddhist monks to the nobility and finally, in the Edo period (1603-1867), to the public. In Japan toothpicks were handmade from the Kuromoji branches and wood, which were found to be giving off an antiseptic, breath freshening lemony taste. Because of the ‘bite’ and pleasant aroma Kuromoji toothpicks were believed to expel bad “ki” (energy) and were sold at numerous toothpick shops on the main streets: Asakusa in Tokyo, Shijo in Kyoto, and Dotonbori in Osaka. These shops and some famous yoji users (i.e. actors and courtesans) were portrayed in the ukiyoe, the woodblock prints of the Edo period!

Established in 1704, ‘Saruya’ in Tokyo is the only shop in Japan still specializing in traditional toothpicks.

Kuromoji and Japanese Way of Tea:

It is said that great Japanese master of the chanoyu (tea ceremony) – Sen no Rikyu (1522-1591) – was fond of ‘black yo-ji’ (Kuromoji toothpick).

Youji – Kuromoji skewer

During the traditional tea ceremony pretty ‘youji’ (sweet picks / skewers) made of Kuromoji wood are still served with the confectionary to the guests. They are used to lift the sweet to one’s mouth or to break the cake up if it is too large to be eaten whole. The picks are meant for single use and may be kept by the guests as souvenirs of the gathering. In fact ‘Kuromoji’ is another name for a cake/sweet pick.

The development of the tea ceremony in the 16th century led to the increased interest in the surrounding grounds. The elegant fences became important elements of tea ceremony gardens. Kuromoji branches and stems provided material for exquisite and expensive ‘spicebush fences’ – Kuromoji-gaki.

Kuromoji-yu: Easy to carve wood never seems to lose its delightful fragrance and it is known that even old, dried up branches give off a truly wonderful scent when broken. Freshly cut Kuromoji twigs are also used for indoor decorations or to produce shavings for an aromatic bath. Due to the relaxing aroma all other parts of the Kuromoji tree are used in bathing too – flowers, leaves, roots, bark and twigs. Relaxing Kuromoji-yu (Kuromoji bath) is believed to be good for eczema and other skin complaints. Some hot spring resorts use Kuromoji essential oil to ‘aromatize the whole property’.

Essential oil of Kuromoji: All parts of spicebush contain volatile oil but Kuromoji essential oil is obtained by steam distillation of leaves and young shoots. The oil is light to dark yellow in colour and has a characteristic, fresh, balsamic aroma slightly reminiscent of rosewood with a hint of myrtle and eucalyptus. The dry-out is fresh, slightly woody and reminiscent of lavender and eucalyptus. Specific gravity at 20C is 0.891

Some sources state that Lindera essential oil (Kuromoji) is obtained by steam distillation of the leaves of the evergreen trees Lindera umbellata, L. membranacea and L. sericea. Other list Lindera umbellata and Lindera fercia but this doesn’t seem to be accurate. Lindera umbellata is in fact deciduous and different Japanese names apply to each variety, which would most probably reflect in the name of the oil (see Taxonomy). It is however possible that few of the 7 varieties of Lindera umbellata are used in production of the essential oil.

The oil was introduced into European commerce by Schimmel & Co. in 1889. It was produced mainly in Azu during the World War II, and was an important raw material for linalool production. Essential oil wildly available now originates mainly from Izu area.

Therapeutic properties of Kuromoji essential oil: Essential oil of Kuromoji has been used traditionally for neuralgia, stiff neck and back pain and for ‘cold intolerance’. It is believed to be gentle and healing to the skin making it a good remedy for eczema and a popular ingredient of soaps, shampoos and lotions. It is relaxing without being sedative, warming, antibacterial, antiseptic and it might be useful in treatment of various respiratory complaints.

Chemical composition of Kuromoji essential oil: the producers of the Kuromoji essential oil list the following major components:

- Terpenes:

limonene 12.61%, alpha-pinene 3.24%, gamma-terpinene 1.40%, camphene 0.86%, beta-pinene 0.56%, beta-caryophyllene 0.48%, terpinolene 0.39%, elemene 0.25% - Alcohols:

linalool 34.31%, geraniol 6.27%, alpha-terpineol 1.81%, nerolidol 1.65% - Esters:

geranyl acetate 12.56% - Oxides:

1,8-cineole 3.93%, linalool oxide 0.74% - Ketones:

camphor 0.30%

At the time of writing, there are no known hazards or contraindications associated with this oil.

Comparisons between Kuromoji and Rosewood essential oils: Lindera umbellata belongs to the Lauraceae botanical family – the same as Cinnamon, Ho and Rosewood. Some sources consider Kuromoji a ‘high linalool containing essential oil’ listing the linalool content at 50-70% making it comparable with rosewood, which typically contains around 85% of linalool. However, the Izu Kuromoji oil has much lower linalool content at 34.31% – slightly lower then Neroli -making its chemical composition considerably different from rosewood’s.

Kuromoji and Herbalism: Various parts of the spicebush are used as herbal remedies. The roots, root bark and xylem have been used as a crude drug in traditional Chinese medicine. Kuromoji root (choushou) is used for cough, rheumatism, arthritis, athlete’s foot, eczema and gastroenteritis. It is greatly respected for its antiseptic and anti-inflammatory properties. Kuromoji bark (ushou) is also used. It is thought to have sedative-hypnotic, anti-tussive and expectorant qualities. Kuromoji tea (from dried leaves) is believed to have therapeutic properties similar to those of the bark and is recommended to people who ‘always feel cold’.

Pricing: Japanese shops are offering Kuromoji essential oil for ¥2415 for 1ml making it a rather expensive essential oil at about £14 per ml

Bibliography:

Herbs, Spices, and Medicinal Plants by Lyle E. Craker, James E.Simon

The New Perfume Book by Nigel Groom

Essential Oils Handbook by H.Panda

T. Burfield – various documents

Folklore Studies’ By S.V.D. Research Institute, Fu jen ta hsüeh (Peking, China) Jên lei hsüeh po wu kuan, Societas Verbi Divini, Society of the Divine Word, JSTOR, Vol.11 1952

Special thank you to my friends Kyoko Tani and Naoko Makino – without you this article would have never happened – and to Akiko Ikariya-san for supplying additional sample of Kuromoji essential oil. Arigato!

First published in The Aromatherapy Times, 2009